Blue and beyond

I’ve just completed my first London’s painting. London’s because it was made here and because it was inspired by one of the first photos that I took in the city, at Barbican. Those who know me know that I’m crazy for some architectural styles, and before I left, there were many friends who recommended me to go back to the Barbican Center. Once I moved to London, however, it was by chance that I came across its towers and its imposing forms, and perhaps this made our first meeting even more special. It rained (“obviously” you’d say, but I assure you that the gray days were fewer than the ones of sun, at least in my perception) and its volumes have stood before me in all their sobriety colour shade, alongside with the green vegetation in the pond, made more vivid by the humid air. The green of the aquatic plants moved to the sky, then covered by two coatings of white painting, the resulting painting a simphony of Liquitex Prussian blue. I would never have cited the brand if I wouldn’t have read it in the caption of one of the works exhibited in the “The American Dream Pop To the Present” exhibition one of Tom Wesselmann’s “Great American nude”. Why specify the brand instead of simply state that it is an acrylic painting? Maybe because “Liquitex was the first water based acrylic paint created in 1955”? Maybe. One thing it’s true for sure, that “The American Dream Pop to the Present” exhibition is full of “prime times,” as when my new friend and philosopher Giulia asked me why I paint buildings.

As always, the questions posed by those who look at my paintings are an opportunity to discover new things about myself and my work. I still have no answer (Giulia asked me only this morning) but in order to build it I’ve decided to visit the Hokusai exhibition with a specific goal in mind: looking at how the Japanese master portrayed the architecture. With the viatic of the recent visit to the show “The Japanese house” (at the Barbican center, so much to stay on the subject) I searched for houses, terraces and windows in Hokusai’s work.

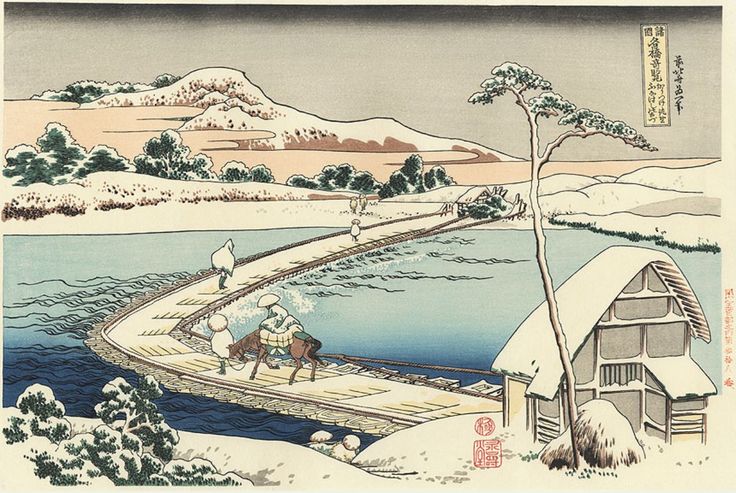

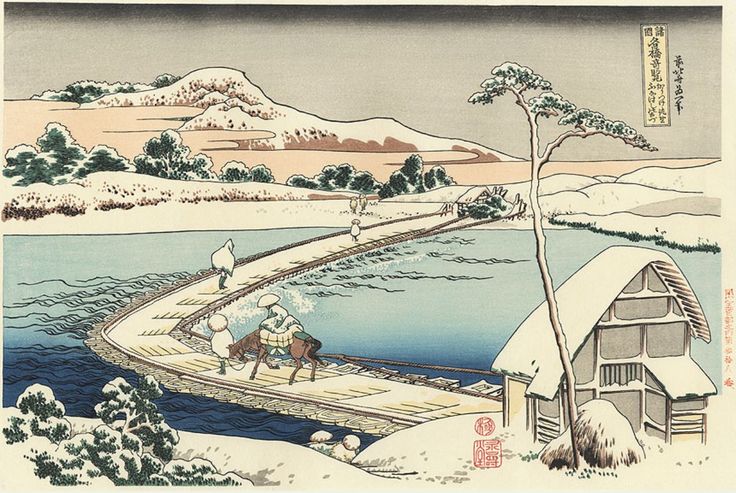

His favourite buildings were the bridges, as proved by the “Wondrous views of famous bridges in various provinces” (c. 1834) series, and example of which is on display here. In it we can recognize the two buildings at the two extremes of the bridge.

In “Year-end accounts”, the artist’s attention is focused one every single aspect of everyday life, as shown by the careful rendering of the various surfaces of a bourgeois interior. Hokusai was convinced that all phenomena had a spirit and they were linked to each other, hence the profound pursuit of the “form of things”, which brings the artist to portray the daily life as if it were extraordinary and so inviting each one of us to perceive ourselves as one thing with the world that surrounds us.

In “Poet Abe no Nakamaro” the poet from the title is sitting on what could be the terrace of the Japanese embassy in China, where he lived for a long time. The architectural element occupies almost half of the work and, in the lower left corner, they work as a scenary flat, thus inviting us to gradually enter the scene and perceive the atmosphere of a sweet evening where the moon, such an immanent presence, is a catalyst for memories and capable of let the mind fly beyond what is visible.

The building performs the same function of directing the viewer’s view in “Sazai Hall, Five Hundred Arhat Temple” where pilgrims, climbing three spiral staircases, can admire Mount Fuji in all its grandeur.

In “Fuji seen in the distance from the Senju pleasure quarter” architecture plays an important role, accompanying us, together with the marching soldiers, along the orderly quarters of physical pleasure, to the contemplation of the majesty of nature. The natural element floats, parallel to the built, throughout the composition. In the foreground a tree to counter-color the roof; The road between the paddles, dotted with ponds, whose shape is identical to the clouds gently caressing the mountains.

“Myoken Hall” portrays faithful people who worship the pine tree where the goddess is said to appear. The artist’s happy touch tells of a reluctant relationship among humankind, buildings and nature.

Finishing with non-Japanese houses, in “Picture of famous places in China” where homes are represented as small triangles, to form towns. China at the time was seen as a place of imagination, conceived as a cradle of ancient cultures and wisdom.

At the end of my visit I recall the things studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, in particular the influence that the Japanese prints of the “floating world” had on artists such as Manet, giving it a new way to conceive the framing of the scenes to be portrayed on canvas. And to think that, almost at the same time, Hokusai was fascinated by European culture, so much to write the title and his signature in “Fast skiffs navigating large waves” imitating Dutch handwriting. The use of Prussia’s blue paint was seen as highly fashionable at the time for the same reason.

To return to the present I pampered myself watching one of the movies from the series dedicated to the exhibition “The American dream pop to the present”: “The inherent vice” by Anderson, taken from the novel by T. Pynchon. Long, nonsensical and funny, the movie is a pendant for the California-based section of exhibition, but in one of the crucial scenes here it is: a huge reproduction of Hokusai’s “Big Wave”. The Great Wave pops to the present, as it has been in for nearly 200 years.

The following text was written by Giulia Corti after her visit at the exhibition “Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave“.

…until the age of 70, nothing I drew was worthy of notice. At 73 years I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects and fish. Thus when I reach 80 years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at 90 to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at 100 years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at 110, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive.

Hokusai arrives at the British Museum with an exhibition that focuses on the last years of his long artistic production and intends to analyze the vision of the world and the context, in which the old master conceives his masterpiece The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

The delicate drawings, the landscapes, the funny faces of the characters represented, refer to many different elements and subjects of inspiration: from Chinese myths and legends, to the rules of the ukiyo-e painting, from the maps of Japanese territory to the still lives and courtesans‘ portraits.

One aspect of the exhibition seems to me particularly fascinating. The selected works allow us to follow Hokusai in his research, or better obsession for the representation of nature. I believe that two are the fundamental elements of this research. On one side, the importance of the concept of time: Hokusai, in the last years of his life, seeks intensively a longer and longer existence in order to have enough time to bring the state of his art to a divine level. On the other side, he claims a precise aim: not only to reach formal perfection in representation, but more ambitiously to reach the essence of things.

In a pantheistic context as the one of Buddhism and Shintoism, the human being is an element of nature on the same level with the other beings. However, Hokusai seems more interested to assume a different point of view: the unique possibility that men have to investigate the order of nature and reach the essence. The aim of observing obsessively the cosmic mechanisms is to harmonize one‘s movement with the one of the universe, without effort or resistance. The meditation and speculative research, that for Hokusai become artistic and expressive research, do not intend to transcend the material and bodily level of things but, on the contrary, to reach a perspective so close to nature to catch the vital and divine forces in it.

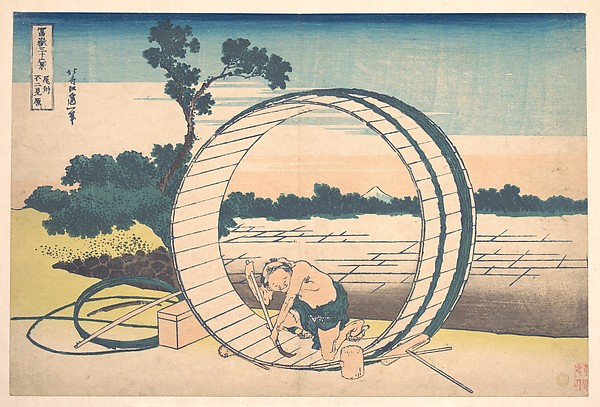

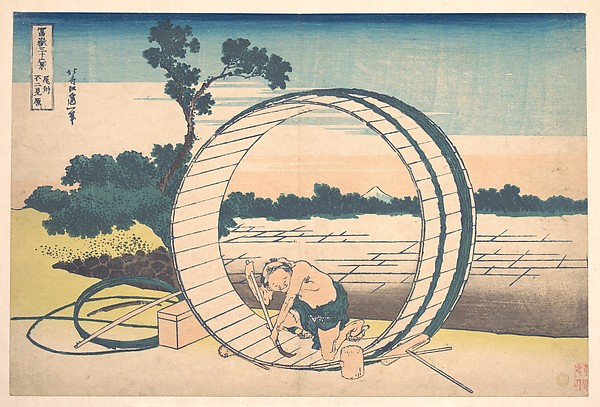

Fuji view Moor in Owari Province (from Thirty Six Views of Mt Fuji), 1823-1829 (circa). The composition seems to suggest an investigation about the position of men within the universe. The circular barrel encloses not only the individual but also the sacred Fuji mountain in the background. This man represents the research of the human’s natural place undertaken through labour.

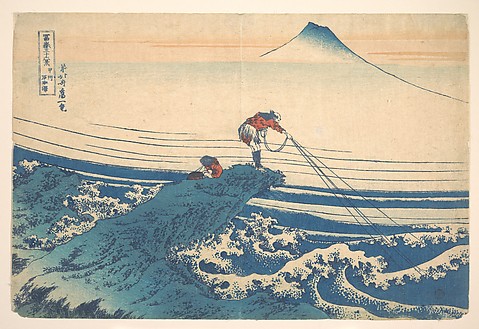

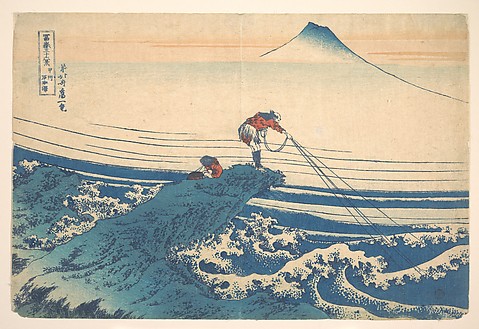

Kajikazawa in Kai Province, (Thirty-six Views of Mt Fuji), 1830-1833. As in the previous work, the man seeks contact with nature through his work. The composition looks harmonic, Mt Fuji is visible in the background, the individual is in the center and the other natural elements (sea, promontory, sky) dissolve in one unique space.

Clearly, the two elements of time and research of the essence are connected. Instead of detaching his person from his body and reach a superior level of existence, as would be more common according to the religious beliefs of this cultural context, Hokusai desires to live longer. This is because what he seems to see as the natural order is essentially movement, change, dynamism. It is not an extra-worldly quiet. The origins of the laws of nature and of the development of the universe are not linear and pacific, but always changing and fostered by contrasts. Hokusai wants to stay alive in order to remain part of this movement and to understand it, go along with it and make it his own rhythm.

Poppies 1833

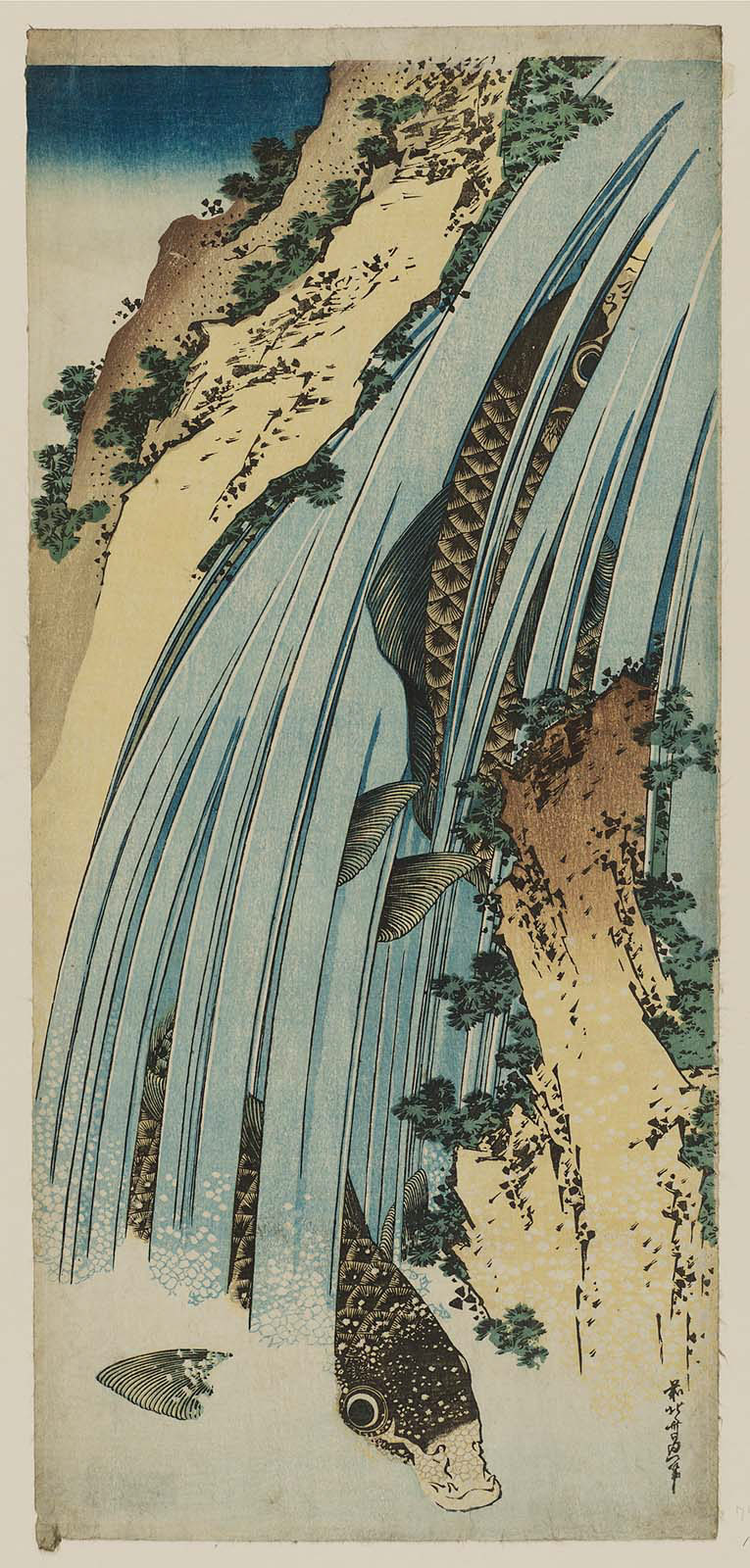

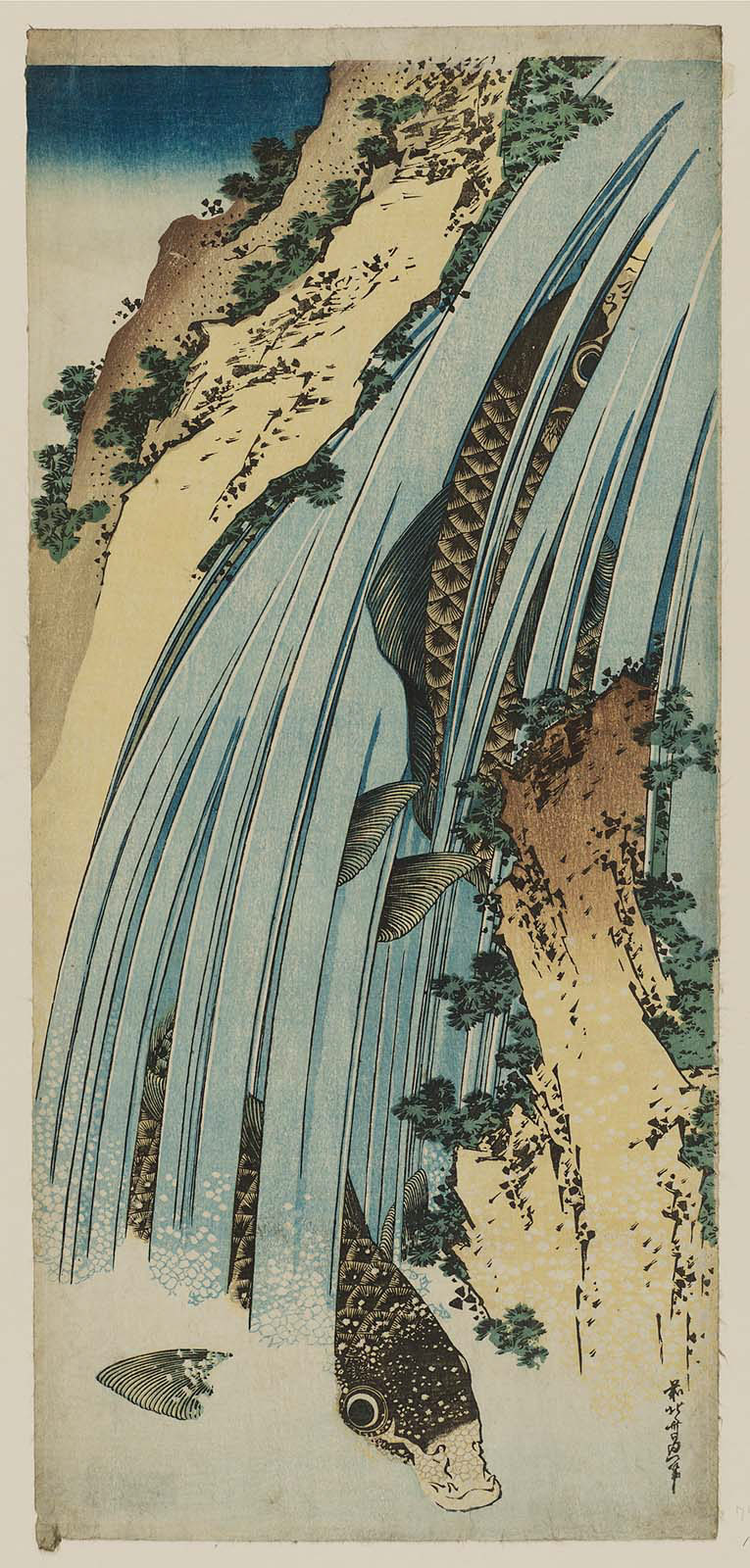

Two Carp in Waterfall, 1834. These works represent in a very clear way the aim of the artistic research of Hokusai: to catch the vital and divine forces inside nature, to see the essence and the forms of things. In the Daoist philosophy, one of the most important references for Hokusai, change is the most fundamental element at the core of every thing. This is the structure of reality: not a form of chaos made orderly and still, but multiplicity and movement.

From this ideas, it seems that for Hokusai art is an instrument of knowledge. In fact, firstly through the productive action in se and secondly with the contemplation of the artwork, the individual can grasp the source of natural forces and, in this way, he can understand his place in this universe.

Giulia Corti in her own words:

I was born in 1993 in Venegono Inferiore, a sparkling small village in the province of Varese, where my family and my childhood friends live. After humanities high school I studied Philosophy at the Catholic University of Milan, where I became passionate about Kant, Nietzsche and Wittgenstein. I moved to London to continue my studies and discovered a city full of opportunities and new precious friends. After completing the master, I took a break from research and by accident I came to work at the British Museum at “The American Dream pop to the present” exhibition. Forced in the very same galleries for hours and hours, I discovered that effective art intrigues, teases and questions. I do not have any artistic training but I like to look around, ask questions and write about some strange things I think.

Completato il mio primo dipinto londinese. Londinese perchè realizzato qui e perchè ispirato a una delle prime foto che ho fatto in città, al Barbican. Chi mi conosce lo sa che una certa architettura mi fa impazzire e, prima che partissi, sono stati molti gli amici che mi hanno raccomandato di tornare al Barbican Centre. Una volta trasferita Londra, però, è stato quasi per caso che mi sono imbattuta nelle sue torri e nelle sue forme imponenti, e forse questo ha reso ancora più speciale il nostro primo incontro. Pioveva (“ovviamente” direte voi, ma vi asssicuro che i giorni grigi sono stati meno numerosi di quelli di sole, almeno nella mia percezione) e i suoi volumi mi si sono parati dinanzi in tutto il loro color sobrietà, accompagnati dal verde della vegetazione nei pressi delle acque, reso brillantissimo dall’aria carica di umidità, tra una pioggerellina e l’altra. Il verde delle piante acquatiche trasferitorisi nel cielo, poi coperto da due mani di bianco, il quadro una sinfonia di blu di Prussia marca Liquitex. Non avrei mai citato la marca del colore se non ne avessi letto nella didascalia di uno dei lavori esposti nella mostra “The American dream pop to the present”, uno della serie “Great American nude” di Tom Wesselmann. Perchè specificare il brand e non informare semplicemente che si tratta di un dipinto ad acrilico? Forse perchè “Liquitex è stata la prima vernice acrilica a base d’acqua creata nel 1955”? Forse. Di certo la mostra “The American dream pop to the present” è piena di “prime volte”, come quando la mia nuova amica, e filosofa, Giulia mi ha chiesto perchè io dipinga edifici.

Come sempre accade nella mia ricerca artistica, le domande poste da chi osserva i miei quadri sono l’occasione per scoprire nuove cose su me stessa e sul mio lavoro. Non ho ancora una risposta (la domanda mi è stata posta solo stamattina), ma per cominciare a costruirla ho deciso di andare a visitare la mostra di Hokusai con un obiettivo ben preciso in mente: osservare come il maestro ritraesse il costruito. Con il viatico della recente visita alla mostra “The Japanese house” (al Barbican centre, tanto per rimanere in tema) ho cercato, nei lavori del maestro giapponese, le case, le terrazze, le finestre.

Tra le architetture Hokusai prediligeva i ponti, come testimonia la serie “Wondrous views of famous bridges in various provinces” (circa 1834) di cui in mostra vi è un esempio dove si possono riconoscere anche le due costruzioni ai due estremi del ponte.

In “Year-end accounts”, si apprezza l’attenzione dell’artista per ogni singolo aspetto della vita quotidiana, testimoniato da un’attenta resa delle diverse superfici di un interno borghese. Hokusai era convinto che tutti i fenomeni avessero uno spirito e fossero legati gli uni agli altri, da qui l’approfondita ricerca della “forma delle cose”, che porta l’artista a ritrarre il quotidiano come se fosse straordinario e così invitando ciascuno di noi a sentirsi tutt’uno con il mondo che ci circonda.

In “Poet Abe no Nakamaro” il poeta del titolo è seduto su quella che potrebbe essere la terrazza dell’ambasciata giapponese in Cina, dove egli ha risieduto a lungo. L’elemento architettonico occupa quasi metà dell’opera e, nell’angolo in basso a sinistra, fa da quinta scenografica, invitandoci in questo modo, ad entrare gradualmente nella scena e a percepire l’atmosfera di una sera dolce, dove la luna, presenza immanente, è catalizzatrice di ricordi e capace di far volare la mente oltre il visibile.

Il costruito svolge la medesima funzione di dirigere lo sguardo dello spettatore in “Sazai hall, Five hundred Arhat temple” dove i pellegrini, salite tre rampe di scala a chiocciola, possono ammirare il monte Fuji in tutta la sua imponenza.

In “Fuji seen in the distance from Senju pleasure quarter” l’architettura svolge un ruolo importante, accompagnandoci, insieme ai soldati in marcia, lungo gli ordinati quartieri del piacere fisico, fino ad arrivare alla contemplazione della maestosità della natura. L’elemento naturale si dipana, parallelo al costruito, lungo tutta la composizione. In primo piano un albero a fare da contraltare cromatico al tetto; la strada tra le risaie punteggiate dagli specchi d’acqua, la cui forma ritroviamo identica sfiorare le montagne, stavolta a rappresentare le nuvole.

“Myoken hall” ritrae fedeli che adorano l’albero di pino dove si dice che la divinità apparisse. La felice mano dell’artista racconta di un rapporto senza cesure tra l’uomo e ciò che egli costruisce e la natura e ciò che essa rappresenta.

Per finire delle case non giapponesi, in “Picture of famous places in China” dove le abitazioni sono rappresentate come piccolissimi triangoli, a formare delle cittadine. La Cina al tempo era vista come luogo dell’immaginazione, pensata come culla di culture antiche e di saggezza.

Al termine della visita mi tornano alla mente le cose studiate all’Accademia di Belle Arti, in particolare l’influenza che le stampa giapponesi del “mondo fluttuante” ebbero su artisti come Manet, dando il la a un nuovo modo di concepire l’inquadratura delle scene da ritrarre su tela. E pensare che, quasi nello stesso momento, Hokusai era affascinato dalla cultura europea, tanto da inserire titolo e firma in “Fast skiffs navigating large waves” imitando la scrittura a mano olandese; e che l’utilizzo del blu di Prussia era visto come di gran moda per lo stesso motivo.

Per ritornare nel presente mi concedo un film della serie dedicata alla mostra “The American dream pop to the present”: “The inherent vice” di Anderson, tratto dal romanzo di T. Pynchon. Lungo, delirante e divertente, il film fa idealmente da pendant alla sezione della mostra dedicata alla California, ma ecco comparire, in una delle scene cruciali, un enorme riproduzione della “Grande onda” di Hokusai. La Grande Onda pop to the present, come sta facendo da quasi 200 anni.

Il testo che segue è stato redatto da Giulia Corti in seguito della sua visita alla mostra “Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave”.

…until the age of 70, nothing I drew was worthy of notice. At 73 years I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects and fish. Thus when I reach 80 years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at 90 to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at 100 years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at 110, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive.

Hokusai arriva al British Museum in una mostra che si concentra sugli ultimi anni della sua lunga produzione artistica e si propone di approfondire la visione del mondo e il contesto in cui il vecchio maestro concepisce la sua opera piú famosa: la Grande Onda di Kanagawa.

I disegni delicati, i paesaggi, le buffe espressioni dei personaggi che vengono rappresentati fanno riferimento a diversi elementi e soggetti di ispirazione: dai miti e le leggende cinesi, ai canoni della pittura ukiyoe, dalle mappe del territorio giapponese a nature morte e ritratti di cortigiane.

Un particolare della mostra mi sembra molto affascinante. Le opere selezionate permettono infatti di seguire Hokusai nella sua ricerca, o meglio ossessione per la rappresentazione della natura. Credo che siano due le caratteristiche fondamentali di questa ricerca. Da una parte il ruolo del tempo: Hokusai negli ultimi periodi della sua vita cerca compulsivamente di propiziarsi un’esistenza ancora piú lunga, in modo da avere tempo abbastanza per portare la sua arte a uno stato divino. Dall’ altra, un obiettivo ben preciso: non solo raggiungere la perfezione formale nella rappresentazione ma piú ambiziosamente riuscire a cogliere l’essenza delle cose.

In un contesto panteista come quello delle religioni buddhista e shintoista, l’uomo ѐ un elemento della natura alla pari con gli altri esseri animati e inanimati. Hokusai peró sembra piú interessato a sfruttare la possibilitá unica che l’uomo ha di indagare lʼordine della natura e coglierne lʼessenza. Il fine di osservare ossessivamene i meccanismi cosmici ѐ quello di accordare il proprio movimento a quello dellʼuniverso, senza piú opporre resistenza. La meditazione e la ricerca speculativa, che per Hokusai diventano ricerca artistica e espressiva, non hanno in questo caso lʼobiettivo di trascendere il livello delle cose materiali e corporee ma al contrario, di farsi cosí vicino alla natura da cogliere le forze vitali e divine in essa.

- Fuji-view Moor in Owari Province, (Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji), 1823-1829 (circa). La composizione sembra suggerire una riflessione sulla posizione dellʼuomo nel cosmo. Il barile circolare racchiude non solo l’uomo ma anche il Monte Fuji in lontananza, luogo spirituale e di devozione. Lʼuomo cerca il suo luogo naturale attraverso il lavoro.

- Kajikazawa in Kai Province, (Thirty-six Views of Mt Fuji), 1830-1833. Come nellʼopera precedente, lʼuomo cerca il contatto con la natura attraverso il lavoro. La composizione ѐ armonica, con il Monte Fuji sullo sfondo, lʼuomo al centro e gli altri elementi naturali (il mare, il promontorio, il cielo) si confondono in un unico ambiente.

In definitiva, i due elementi del tempo e della ricerca dellʼessenza sono collegati. Hokusai desidera vivere piú a lungo anzichѐ distaccarsi dal corpo e ascendere a un tipo superiore di esistenza- come sarebbe piú comune nelle credenze religiose di questo contesto. Questo perchѐ ció che lui sembra vedere come ordine della natura ѐ essenzialmente un movimento, un cambiamento, un dinamismo. E non una quiete extra-mondana. L’origine delle leggi di natura e dell’andamento dell’ universo non sono lineari e pacifiche, ma mutano e sono alimentate dai contrasti. Hokusai vuole rimanere in vita per continuare a prendere parte a questo movimento e capirlo, assecondarlo e farlo proprio.

Poppies, 1833

Two Carp in Waterfall, 1834.

Le opere rappresentano in modo molto forte lʼobiettivo della ricerca artistica di Hokusai: cogliere le forze vitali e divine nella natura, vederne lʼessenza, le forme di vita. Nella filosofia Daoista -uno dei riferimenti piú importanti per Hokusai- il cambiamento e il movimento sono i caratteri fondamentali alla base di tutte le cose. Questa ѐ la struttura della realtá, non caos reso immobile e ordinato, ma molteplicitá e movimento.

Da queste prime riflessioni, sembrerebbe che per Hokusai l’arte sia strumento conoscitivo. Attraverso l’azione produttiva in se e poi anche la contemplazione dell’opera, l’uomo puó arrivare a conoscere la sorgente delle forze e dell’ordine naturale e in questo modo concepire anche il suo posto in questo universo.

Giulia Corti dice di sè:

sono nata nel 1993 a Venegono Inferiore, un frizzante piccolo paese della provincia di Varese, dove vivono la mia famiglia e i miei amici di infanzia. Dopo il liceo classico ho studiato Filosofia all’Università Cattolica, e mi sono appassionata di Kant, Nietzsche e Wittgenstein. Da Milano sono partita per Londra, dove ho continuato a studiare e ho incontrato una città piena di opportunità e soprattutto di nuovi amici preziosi. Una volta ultimato il master, mi sono presa un anno di pausa dallo studio e per caso sono capitata a lavorare al British Museum nella mostra The American Dream. Costretta fra le gallerie per ore e ore o scoperto che l’arte efficace incuriosisce, stuzzica e interroga. Non ho nessuna formazione artistica ma mi piace guardarmi intorno, farmi delle domande e scrivere di alcune cose strane che penso.

-----------------Published on 24-May-2017

Tags: american dream, American dream pop to the present, art, barbican, blue, British Museum, giulia corti, great wave, hokusai, japanese house, liquitex, manga, marycinque, philosophy, pop art, titled

Blue and beyond